So this post is centered around a video-response micro-project for my MA course module. The video in question can be viewed below:In the Cut, Part I: Shots in the Dark (Knight) from Jim Emerson on Vimeo.

In response, I set about to re-storyboard the Dark Knight convoy sequence, from my own perspective, to help answer the visual 'problems' as proposed by this video, whether they are valid or not. The boards are extremely rough (as was the overall exercise), but nonetheless hope to communicate effectively some of the alternatives I have offered. You will notice that many frames mirror precisely the original scene; this is not done in laziness but rather where I felt that what was given was the natural way to shoot it. In other frames, however, I have opted for different approaches, with short explanations given.

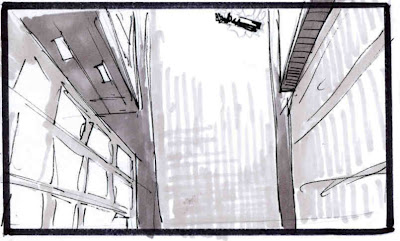

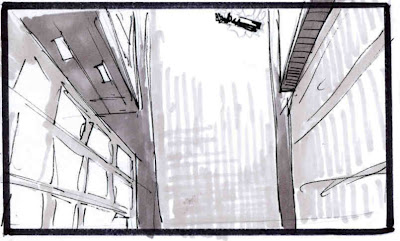

Frame 1, scene 1. The convoy moves out. Aerial shot. Helicopter enters frame.

Frame 2, scene 2. Top-shot. Convoy progresses down the darkened avenue of Gotham.

Frame 2, scene 2. Top-shot. Convoy progresses down the darkened avenue of Gotham.

Frame 3, scene 2-cont. Camera drifts ahead of the convoy; flaming obstruction revealed.

Frame 3, scene 2-cont. Camera drifts ahead of the convoy; flaming obstruction revealed.

Frame 4, scene 3. Medium shot, profile. The front two cops of the convoy notice.

Frame 4, scene 3. Medium shot, profile. The front two cops of the convoy notice.

Frame 5, scene 3-cont. Interior shot, POV of the obstacle; a fire truck ablaze.

Frame 5, scene 3-cont. Interior shot, POV of the obstacle; a fire truck ablaze.

Frame 6, scene 4. Low angle; the convoy pulls past the camera to the right; first SWAT van comes into view.

Frame 6, scene 4. Low angle; the convoy pulls past the camera to the right; first SWAT van comes into view.

Frame 7, scene 5. Medium shot, profile; SWAT cops watch apprehensively.

Frame 7, scene 5. Medium shot, profile; SWAT cops watch apprehensively.

Frame 8, scene 6, Top-shot; convoy diverts around the obstruction.

Frame 8, scene 6, Top-shot; convoy diverts around the obstruction.

Frame 9, scene 7; POV interior; convoy continues to divert the blazing fire truck.

Frame 9, scene 7; POV interior; convoy continues to divert the blazing fire truck.

Frame 10, scene 7- cont. Camera tracks to the right, locked on the fire truck.

Frame 10, scene 7- cont. Camera tracks to the right, locked on the fire truck.

Frame 11, scene 8. High-angle; the convoy drops down onto 'lower fifth' on the left side of frame.

Frame 11, scene 8. High-angle; the convoy drops down onto 'lower fifth' on the left side of frame.

Frame 12, scene 9. Medium CU; Front Cop driver spots something in his rear-view.

Frame 12, scene 9. Medium CU; Front Cop driver spots something in his rear-view.

Frame 13, scene 10. Medium-wide; from top left a truck speeds alongside the cruiser.

Frame 13, scene 10. Medium-wide; from top left a truck speeds alongside the cruiser.

Frame 14, scene 10-cont. Camera drifts to the left; truck slams into the side of the cruiser.

Frame 14, scene 10-cont. Camera drifts to the left; truck slams into the side of the cruiser.

Frame 15, scene 11. Top-shot. Cruiser swings out to the left from the impact, the truck hurtles on.

Frame 15, scene 11. Top-shot. Cruiser swings out to the left from the impact, the truck hurtles on.

Frame 16, scene 12. Wide. Top right: cruiser in the background skids out of view, colliding with the pillars; Center: Truck speeds up against the second cruiser in the foreground.

Frame 16, scene 12. Wide. Top right: cruiser in the background skids out of view, colliding with the pillars; Center: Truck speeds up against the second cruiser in the foreground.

Frame 17, scene 12-cont. Camera drifts to the left; front cruiser swerves as the truck rams the boot.

Frame 17, scene 12-cont. Camera drifts to the left; front cruiser swerves as the truck rams the boot.

Frame 18, scene 13. Top-shot. Cruiser swings round to the left, bottom of frame; truck hurtles on.

Frame 18, scene 13. Top-shot. Cruiser swings round to the left, bottom of frame; truck hurtles on.

Frame 19, scene 14. Medium-wide, interior. Dent and SWAT member look nervously to the BACK of the SUV.

Frame 19, scene 14. Medium-wide, interior. Dent and SWAT member look nervously to the BACK of the SUV.

Frame 20, scene 15. Truck hurtles towards camera.

Frame 20, scene 15. Truck hurtles towards camera.

Frame 21, scene 16. Truck rams into the back of the SUV.

Frame 21, scene 16. Truck rams into the back of the SUV.

Frame 22, scene 17. Medium CU, interior. Dent reacts to the jolt, looking to the RIGHT.

Frame 22, scene 17. Medium CU, interior. Dent reacts to the jolt, looking to the RIGHT.

Frame 23, scene 18. Same angle, meduim CU. SWAT member looks to his driver, ''Get a move on!''

Frame 23, scene 18. Same angle, meduim CU. SWAT member looks to his driver, ''Get a move on!''

Frame 24, scene 19. High-angle; the remainder of the front convoy hurtles beneath camera, pursuing truck in tow.

Frame 24, scene 19. High-angle; the remainder of the front convoy hurtles beneath camera, pursuing truck in tow.

Frame 25, scene 20. Medium-wide. SUV driver calls to his SWAT team, ''Buckle up guys.''

Frame 25, scene 20. Medium-wide. SUV driver calls to his SWAT team, ''Buckle up guys.''

Frame 26, scene 21. SUV hurtles past from left to right.

Frame 26, scene 21. SUV hurtles past from left to right.

Frame 27, scene 22 (iteration 1). Reverse cut; Larger truck enters frame from left for a collision with the SUV, entering right side.

Frame 27, scene 22 (iteration 1). Reverse cut; Larger truck enters frame from left for a collision with the SUV, entering right side.

Frame 27, scene 22 (iteration 2). Large truck enters from center for collision; SUV enters frame from right.

Frame 27, scene 22 (iteration 2). Large truck enters from center for collision; SUV enters frame from right.

Frame 28, scene 22-cont. Reverse shot. They collide; SUV is smashed off-course.

Frame 28, scene 22-cont. Reverse shot. They collide; SUV is smashed off-course.

Frame 28, scene 22-cont (iteration 3). Medium-CU. Tighter show of the impact.

Frame 28, scene 22-cont (iteration 3). Medium-CU. Tighter show of the impact.

Frame 28, scene 22-cont (iteration 4). Medium-wide. Truck collides with the back end of the SUV, swinging it out left-side of frame.

Frame 28, scene 22-cont (iteration 4). Medium-wide. Truck collides with the back end of the SUV, swinging it out left-side of frame.

Frame 29, scene 22-cont. Top-shot. Large truck cuts through the trajectory of the convoy; collided SUV swings out to the right.

Frame 29, scene 22-cont. Top-shot. Large truck cuts through the trajectory of the convoy; collided SUV swings out to the right.

Frame 30, scene 23. (same angle as frame 25). Reaction shot.

Frame 30, scene 23. (same angle as frame 25). Reaction shot.

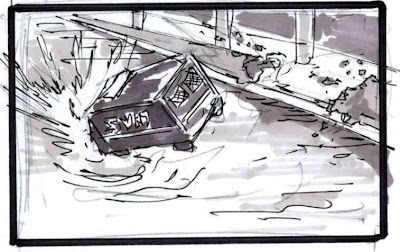

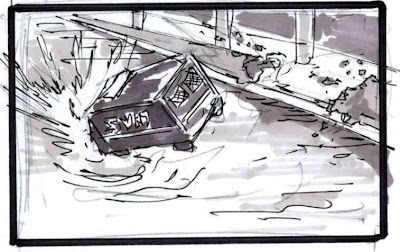

Frame 31, scene 24 (iteration 1). Medium-wide. SUV smashes through the underpass barrier into the river.

Frame 31, scene 24 (iteration 1). Medium-wide. SUV smashes through the underpass barrier into the river.

Frame 31, scene 24 (iteration 2). Extreme wide.

Frame 31, scene 24 (iteration 2). Extreme wide.

Frame 32, scene 25. Interior, POV/Over-the-shoulder. Rear SUV drivers observe the Large truck swinging in-front of them.

Frame 32, scene 25. Interior, POV/Over-the-shoulder. Rear SUV drivers observe the Large truck swinging in-front of them.

Frame 33, scene 26. Top-shot. SUV repositions to the right-side of the Large truck.

Frame 33, scene 26. Top-shot. SUV repositions to the right-side of the Large truck.

Frame 34, scene 27. Medium CU, interior. Dent waits apprehensively.

Frame 34, scene 27. Medium CU, interior. Dent waits apprehensively.

Frame 35, scene 27 cont. Reverse shot. SWAT cop remains inscrutable.

Frame 35, scene 27 cont. Reverse shot. SWAT cop remains inscrutable.

Frame 36, scene 28. Wide. Large truck and SUV are positioned alongside each other; visual gag is revealed: LAUGHTER is the slogan on the side, with a crudely spray-painted S at the start.

Frame 36, scene 28. Wide. Large truck and SUV are positioned alongside each other; visual gag is revealed: LAUGHTER is the slogan on the side, with a crudely spray-painted S at the start.

Frame 37, scene 28-cont. Jump Cut. Large truck door slides open; the Joker and his thugs are finally revealed.

Frame 37, scene 28-cont. Jump Cut. Large truck door slides open; the Joker and his thugs are finally revealed.

Frame 38, scene 28-cont. Joker fires a few rounds, aimed off-frame to the right.

Frame 38, scene 28-cont. Joker fires a few rounds, aimed off-frame to the right.

Frame 39, scene 29. Reverse angle. Bullets riddle the armoured SUV.

Frame 39, scene 29. Reverse angle. Bullets riddle the armoured SUV.

Frame 40, scene 30. Medium shot. SWAT member flinches as the bullets dent the inside of the van.

Frame 40, scene 30. Medium shot. SWAT member flinches as the bullets dent the inside of the van.

Frame 41, scene 30-cont. Medium-wide. Orientational shot; Dent sits RIGHT, SWAT member sits LEFT with bullet dents behind.

Frame 41, scene 30-cont. Medium-wide. Orientational shot; Dent sits RIGHT, SWAT member sits LEFT with bullet dents behind.

Frame 42, scene 31. Small truck rams into the back of the SUV.

Frame 42, scene 31. Small truck rams into the back of the SUV.

Frame 43, scene 32-cont. Top-shot. Large truck and small truck hem in the lone SUV.

Frame 43, scene 32-cont. Top-shot. Large truck and small truck hem in the lone SUV.

Frame 44, scene 33. Medium-wide. Joker prepares a bazooka.

Frame 44, scene 33. Medium-wide. Joker prepares a bazooka.

Frame 45, scene 34. Low-angle. SUV swerves to the left sharply.

Frame 45, scene 34. Low-angle. SUV swerves to the left sharply.

Frame 46, scene 34-cont. Top-shot. SUV swings into the far lane.

Frame 46, scene 34-cont. Top-shot. SUV swings into the far lane.

Frame 47, scene 35. CU. Joker aims with malicious glee.

Frame 47, scene 35. CU. Joker aims with malicious glee.

Frame 48, scene 35-cont. Over-the-shoulder shot. Joker aims for the distant SUV.

Frame 48, scene 35-cont. Over-the-shoulder shot. Joker aims for the distant SUV.

Frame 49, scene 35-cont. An engine growls into life; Joker is distracted, looking off-frame to the right at the source.

Frame 49, scene 35-cont. An engine growls into life; Joker is distracted, looking off-frame to the right at the source.

Frame 50, scene 36. Reverse shot. Medium CU. SUV drivers look left off-frame at the source, ''Look out!''

Frame 50, scene 36. Reverse shot. Medium CU. SUV drivers look left off-frame at the source, ''Look out!''

Frame 51, scene 37. Extreme wide, high-angle. The Tumbler roars towards the camera.

Frame 51, scene 37. Extreme wide, high-angle. The Tumbler roars towards the camera.

Frame 52, scene 38. Interior, medium CU. The Batman steers the tumbler.

Frame 52, scene 38. Interior, medium CU. The Batman steers the tumbler.

Frame 53, scene 39. CU. Front shot of the fore-wheel spinning; engine growls as momentum is built up.

Frame 53, scene 39. CU. Front shot of the fore-wheel spinning; engine growls as momentum is built up.

Frame 54, scene 40. Joker smiles at the challenge.

Frame 54, scene 40. Joker smiles at the challenge.

Frame 55, scene 41. Medium CU, profile, interior. The Batman remains focused.

Frame 55, scene 41. Medium CU, profile, interior. The Batman remains focused.

Frame 56. scene 43. Tighter shot of frame 54. Joker goads.

Frame 56. scene 43. Tighter shot of frame 54. Joker goads.

Frame 57, scene 44. Low-angle, CU. Rear shot of the Tumbler as flames propel it; large truck dominates left-side of frame, showing the collision course.

Frame 57, scene 44. Low-angle, CU. Rear shot of the Tumbler as flames propel it; large truck dominates left-side of frame, showing the collision course.

Frame 58, scene 45. High-angle. Tumbler hurtles beneath rising camera out of shot.

Frame 58, scene 45. High-angle. Tumbler hurtles beneath rising camera out of shot.

Frame 59, scene 46. Wide. Tumbler hurtles past the Large Truck.

Frame 59, scene 46. Wide. Tumbler hurtles past the Large Truck.

Frame 60, scene 46-cont. Jump cut (or insert). Joker tracks the Tumbler's trajectory, looking left off-frame.

Frame 60, scene 46-cont. Jump cut (or insert). Joker tracks the Tumbler's trajectory, looking left off-frame.

Frame 61, scene 47. Wide. Tumbler collides with the Small Truck, flipping it above into the underpass ceiling.

Frame 61, scene 47. Wide. Tumbler collides with the Small Truck, flipping it above into the underpass ceiling.

Frame 62, scene 48. Top-shot. Tumbler turns around, skidding to the right.

Frame 62, scene 48. Top-shot. Tumbler turns around, skidding to the right.

Frame 63, scene 48-cont. Medium CU. Rear shot of the Tumbler swinging center; flames burst into life propelling it forward.

Frame 63, scene 48-cont. Medium CU. Rear shot of the Tumbler swinging center; flames burst into life propelling it forward.

Frame 64, scene 48-cont. Tumbler zooms away from camera.

Frame 64, scene 48-cont. Tumbler zooms away from camera.

Frame 65, scene 49. Medium wide. Small truck is left demolished and jack-knifed.

Frame 65, scene 49. Medium wide. Small truck is left demolished and jack-knifed.